A recent study published in the journal Royal Society Open Science has illuminated a fascinating aspect of the animal kingdom: Ultraviolet visibility in mammals. This finding refutes the assumption that such ability is possessed by only certain animals. Fluorescence has been extensively documented in various creatures such as corals, insects, spiders, fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds for a long time, but scientists have recorded it in only a few species of mammals.

Nevertheless, new studies reveal that 125 mammalian species are capable of this feat. What purpose this ability serves is not yet known, but still, a remarkable one that is leading us into the fascinating world of fluorescence in mammals!

The Origins of Fluorescence

Fluorescence in animals occurs when specific chemicals absorb short-wavelength ultraviolet light that is invisible to human eyes and emit longer-wavelength, visible light, creating a colorful glow.

These light-emitting chemicals have been discovered in various parts of animals, such as their bones, teeth, claws, fur, feathers, and skin. For instance, European rabbits were the first non-human mammals to exhibit fluorescence, discovered back in 1911.

Fluorescent Mammals

The 2020 discovery of platypuses’ blue-green glow under UV light piqued Kenny Travouillon’s curiosity. Following this revelation, further research was conducted, which found that the quills of hedgehogs, porcupines, certain marsupials like the bilby, and other mammals also exhibited fluorescence.

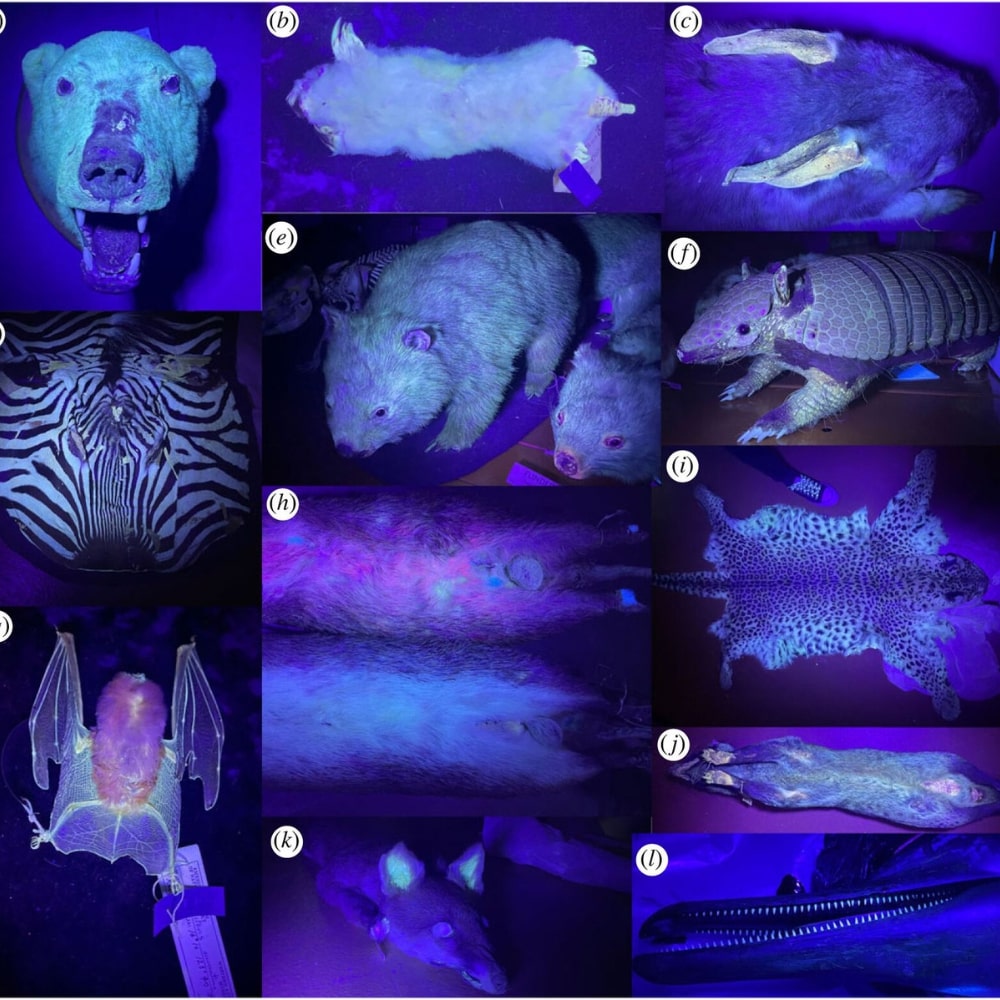

To delve deeper into this fascinating phenomenon, researchers examined 146 specimens—or 125 mammal species from 79 different animal families. Astonishingly, all species exhibited fluorescence to varying degrees. Among the fluorescent mammals, the dwarf spinner dolphin stood out with its glowing teeth, although it did not exhibit fluorescence on its external body.

Potential Evolutionary Functions of Fluorescence

The reasons behind this fluorescence in mammals remain unclear. Scientists propose several theories, one of which suggests that nocturnal mammals might use this glow for communication in low-light conditions.

For instance, carnivores could use the glowing patterns on their backs to recognize members of their own species. However, this theory does not apply universally, as in the case of the southern marsupial mole, which is blind.

The Enigma of Mammals’ Glow

While scientists continue to explore the evolutionary significance of fluorescence in mammals, it seems that this glow may be more of a byproduct of the presence of certain chemicals in their hair and skin rather than an adaptive trait.

As Alistair Evans, an evolutionary developmental biologist at Monash University, points out, it appears that for most, if not all, mammals, fluorescence is a side effect rather than an evolutionarily advantageous feature.